|

RIO DE JANEIRO,

Brazil — This

country, famed for

its development of

sugar-cane-produced

ethanol, soon could

become one of the

world's great oil

powers — if its

state-controlled

energy company,

Petrobras, can tap a

potentially massive

deposit beneath the

South Atlantic

Ocean.

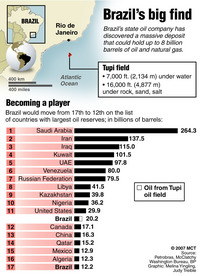

Experts believe

the deposit, in the

Tupi field 180 miles

off the southeastern

Brazilian coast,

holds up to 8

billion barrels of

light oil and

natural gas. If

confirmed, the

deposit would be the

largest petroleum

find in seven years

and would propel

Brazil to the No. 12

position in oil

reserves, after the

United States and

ahead of Canada and

Mexico.

Analysts estimate

that the deposit

could be worth as

much as $60 billion

and predict that

Brazil, which last

year for the first

time produced as

much oil as it

consumed, could

become a major oil

exporter.

|

Yet the find will

challenge Petrobras'

reputation as one of

the world's best at

exploiting deep-sea

oil deposits.

About 70 percent

of Petrobras' oil

production comes

from deep-water

wells, making it the

world's biggest oil

producer at such

depths. But the Tupi

deposit is deeper

than Petrobras has

ever drilled — under

7,000 feet of ocean

water and more than

16,000 feet of rock,

sand and salt,

including a

1.2-mile-thick layer

of rock-hard salt.

How to tap into

the find has set off

a technological

race, spurred

because the

potential rewards of

exploiting the

deposit are so great

— especially as the

price of oil nears

$100 a barrel.

"It's among the

most complicated

projects in the

world in terms of

deep water," said

Caio Carvalhal, a

Brazil-based

research associate

with the U.S.

consulting firm

Cambridge Energy

Research Associates.

"But Petrobras has

proved in the past

that it is up to the

task."

Company officials

have said that years

of planning lie

ahead, and experts

estimate that the

Tupi field won't

start operating

fully until 2013.

Although the company

announced the find

last year, it just

released estimates

of its size in

November. The

company will have to

drill more wells to

better calculate the

size of the deposit.

"This was the

first time that we

arrived at this

depth, and the

technology is

expensive," said

Guilherme Estrella,

Petrobras' director

of exploration and

production. "The

costs are elevated,

but the quality of

the oil brings

robustness and

viability to this

investment."

The Tupi field is

the latest landmark

in a technological

race to the bottom

of the ocean that

many say is the

energy industry's

future.

Already, about a

third of world oil

production is

offshore, with as

much as 15 percent

coming from deep

waters, said energy

consultant David

Llewelyn, who's

worked extensively

in Brazil. Some of

the most promising

offshore oil regions

lie in the so-called

Golden Triangle,

made up of the Gulf

of Mexico and the

coasts of Brazil and

western Africa.

In 2005,

U.S.-based Chevron

and its partners

drilled the deepest

offshore oil and gas

well in history at

34,189 feet below

sea level in the

Gulf of Mexico,

according to

Transocean, the

world's largest

offshore drilling

contractor, which

completed the well.

The deepest onshore

well, at 37,016

feet, was completed

earlier this year on

Sakhalin Island, off

the Russian coast,

for ExxonMobil.

Last year,

Chevron announced it

had found one of the

biggest oil deposits

in the United

States, as much as

15 billion barrels

of petroleum, more

than 28,000 feet

below sea level in

the Gulf of Mexico.

"This is where

the industry has to

go to make the big

finds like this,"

said Thomas Marsh,

the Houston-based

vice president of

the consulting group

ODS-Petrodata, a

world leader in

offshore exploration

analysis. "And a lot

of money is being

spent on getting the

industry going where

it needs to go."

Oil companies

reach such

ultra-deep deposits

by lowering drill

bits into the ocean

floor through a

system of pipes

connected to a

floating platform on

the water's surface.

The pipes and drills

get smaller the

farther into the

ocean floor they

penetrate. At

maximum depth,

they're only about 8

inches wide, which

increases their

chances of being

damaged.

The dangers come

with the intense

water pressure and

heat, which can

damage even the

hardiest of metal

drills. Temperatures

30,000 feet below

the ocean floor can

reach 400 degrees

Fahrenheit, hot

enough to turn oil

into natural gas.

The biggest

technical challenge

of the Tupi deposit

is penetrating the

solid salt layer,

which can become a

kind of gel that

squeezes and resists

the drill bit. The

salt also can

interfere with sound

wave-based seismic

imaging that

engineers use to

figure out what's

below it.

The deposit's

location far from

the Brazilian coast

also complicates the

task of delivering

an estimated 53

million cubic feet

of natural gas daily

to consumers in the

project's pilot

phase.

Because natural

gas can't be stored,

Petrobras might have

to build an enormous

gas pipeline that

would stretch 180

miles to shore or

install gas

liquefaction

facilities above the

deposit to turn the

natural gas into

storable liquid.

Despite all the

difficulties,

Petrobras will rise

to the challenge,

said Marcio Rocha

Mello, president of

the Brazilian

Association of

Petroleum Geologists

and a former head of

the company's

geosciences section.

Before confirming

the Tupi find,

Petrobras already

had drilled 15 wells

into the solid salt

along Brazil's

southeastern coast,

mapping an undersea

basin of oil and gas

stretching about 500

miles long.

"We've already

put a lot of

training and

resources into

this," Rocha Mello

said. "The

technology involved

is already fully

understood. It's not

going to be a

problem."

Drilling the

first well alone

cost $240 million,

and tapping the Tupi

deposit will require

investing at least

$5 billion at the

outset, Llewelyn

said. Petrobras

controls a 65

percent stake in the

deposit, with

British company BG

Group and Portugal's

Gal Energia

controlling the

rest.

Petrobras has

made such

investments pay off

in the past largely

through innovation.

The company

pioneered the use of

floating platforms

to drill wells and

store oil and has

come up with new

ways to heat and

transport extracted

petroleum.

The company has

tried such

technology in more

than two dozen

countries, including

in the United

States, and shared

its know-how with

countries also

looking at going

deep. In the

process, Petrobras

has lowered its

costs for finding

new deposits.

And unlike state

energy companies in

Venezuela and

Mexico, Petrobras is

known as one of the

best-run firms in

the industry.

Innovation has

come with risks,

however, and even

tragedy. In 2001, a

Petrobras rig that

was then the largest

in the world caught

fire and sank off

the Rio de Janeiro

coast, killing 11

people.

Despite such

setbacks and the

enormous investments

required, the Tupi

discovery guarantees

that Petrobras will

be exploring the

ocean floor off the

Brazilian coast for

years to come.

"With a find this

size, the cost isn't

really an issue,"

said energy

consultant

Llewellyn. "You

really just have to

do it."